What science tells us about expertise

Psychologists, cognitive scientists, and AI researchers have for decades grappled with answering: what does it mean to be an expert, and how does someone become one?

To theorize about human ability, science must consider whether expertise is acquired as a result of nature or nurture. Are you born with the capacity to be one of the best, or can you achieve greatness with the right training?

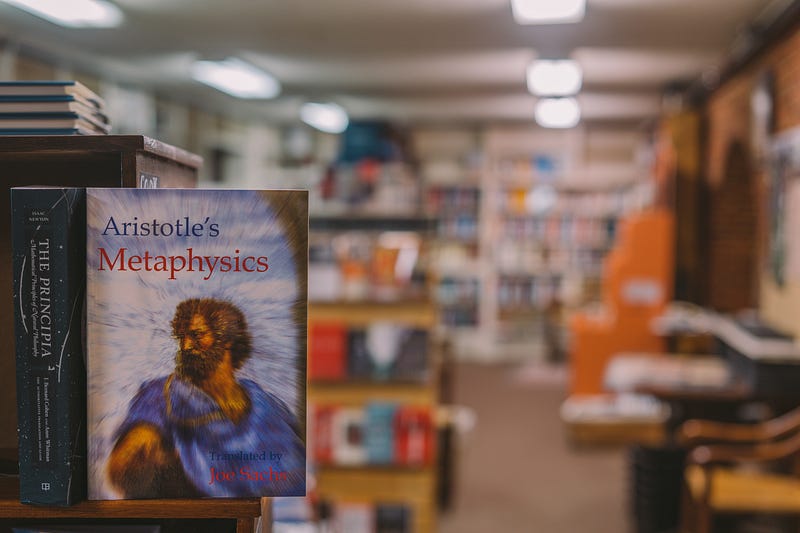

This debate is as old as philosophy itself, with Plato favoring nature, and Aristotle leaning towards nurture.

However, as with all decisions that initially appear to be binary, the argument is usually considerably more nuanced.

Innate talent versus deliberate practice — a difference in timing?

The real difference between innate ability and deliberate practice is the former happens over many generations, while the latter during just one.

To understand what it means to become an expert, we must define deliberate practice and debunk some of the popular myths.

Deliberate Practice

According to research by Anders Ericsson, the acquisition of expertise is a result of long-term, deliberate practice, based on four essential properties:

- The task should be neither too easy nor too hard

- Ongoing feedback must be received by the learner to optimize performance

- The learner has the opportunity to repeat the task

- The learner has the opportunity to correct errors and improve

Gaining experience without focus will not result in expertise. Instead, practice must be with purpose and result from breaking a more significant challenge into a set of smaller ones.

Measurement and feedback are vital to improving skills. In their absence, it is impossible to realign efforts, re-focus energies, and progress.

The quality and the form the deliberate practice takes is considerably more important than the number of hours devoted to performing that task.

In Ericsson’s landmark, 1991 experiment, a group of violinists were divided by ability:

- Outstanding (likely to become international performers as soloists )

- Extremely good (expected to play in top orchestras but not as soloists)

- Good (destined to become music teachers)

The backgrounds of each group were similar, but the volume of training differed considerably. Outstanding violinists — destined to perform as international soloists — on average, completed 10,000 hours of practice. Their training involved 6,000 hours, over and above, those hoping to become music teachers.

According to Ericsson, to be exceptional requires persistent, deliberate practice often over many years.

William Gladwell’s interpretation — made famous in the best seller ‘Outliers’ — was that 10,000 hours of practice is the magic number of hours required to become an expert.

This argument has resulted in the misleading, belief that

Deliberate practice is all that is required, for anyone, to develop expert performance

But this is not what Ericsson concluded from his research.

How does practice help?

According to Ericsson, the benefit of practice is a reduced reliance on limited working memory.

A novice learning, and interpreting, the positions on a chessboard, relies heavily on working memory to store and process information, albeit briefly. The expert utilizes their prior experience and expertise and can store large amounts of information directly in memory.

This increased processing power results in a lower cognitive load and the opportunity to engage in increasingly difficult challenges.

Genetics and Inheritance

The importance of genetic inheritance cannot be underestimated. The biological adaptations humans have inherited impact all sports, skills, and challenges in which humans engage.

In 2003, after 13 years of rigorous research, teams of scientists (part of the Human Genome Project), collaborating around the world, completed the mapping of the human genome. However, despite providing information regarding where to look for the roots of human traits, the map did not identify how the body is built to perform.

In the years since, research has been undertaken to better understand the impact of both individual and groups of genes. For example, according to the work of geneticist Claude Bouchard and his team, genetic makeup and complex interaction of multiple genes are critical to athletic ability. Aerobic capacity alone is a result of at least 200 genes.

The challenge remains for science to clarify the integration of both nature and nurture in performance excellence, where that balance lies, and its variation across the many areas of capacity in our species.

Combining nature and nurture and redressing the balance

There is no magic number when it comes to practice. Indeed, many international performers in sports have practiced far below 10,000 hours, often not entering competition until late teens. There are also individuals who have practiced beyond 10,000 hours and never reached elite status.

Ericsson’s 2012 article attempted to address several mistruths and misunderstandings that entered the public domain (likely a result of newsworthy headlines) while integrating expertise into current genetic research.

Ericsson criticized what he described as an overly simplistic view of his work regarding expertise. He rejected the misinterpretation that with a sufficient number of hours practice, any individual will automatically become an expert or a champion.

Ericsson also clarified his position regarding genetics. He did not suggest that genetics plays no part in expertise, but rather that at present, there is no evidence for the influence of genetics on expertise. Indeed in some of his earlier studies, he made the critical point that for many elite athletes height is an essential factor and that this is genetically determined. On the other hand, increased heart size, which tends to identify athletes, is mostly a result of training (though some genetic factors may also play an essential role in the starting size and the effectiveness of the training).

Ericsson also recognized the importance of motivation and enjoyment of activities, their potential underlying genetic influences, and the impact on hard work and deliberate practice.

The ‘10,000-hour rule’ alone is too simple to either identify or predict a top performer and assumes that an expert must have ten years of accumulated practice that adds up to 10,000 hours.

Deliberate practice alone is not sufficient to explain the acquisition of every aspect of expert performance. It is unlikely that all fields of expertise and performance have the same development path.

Furthermore, Ericsson makes clear that a future, more complete understanding, and model, of performance development is only possible by comparing both objective performance measures and genetic and training factors.

Environment and success

Deliberate practice is crucial when it comes to becoming the very best, within the limits of our genetic predispositions. 10,000 hours has no mystical, or secret, performance-enhancing value, but rather is an easily digested headline.

Instead, the right environment, with focussed training, providing clear feedback, will allow us to achieve what is possible. This does not mean we can all be a Serena Williams or Usain Bolt, but does enable progression and goal achievement.

Finally, it is worth considering what we identify as marking top performance, and what success looks like for the individual. The assumption throughout the research is that winning, fame, and accreditation are what characterizes the best. But, for many, success in sport, or in life, is measured by enjoyment, improvement, and happiness.

This article, along with others, was originally published on Medium

Recent Comments